Fighters in Gaza launched a barrage of rockets toward Israel and in the direction of al-Ahli Hospital 44 seconds before an explosion there that killed at least 100 people, according to a visual analysis by The Washington Post.

A barrage and a midair explosion: What visual evidence shows about the Gaza hospital blast

Videos analyzed by The Post reveal that rockets were launched from Gaza in the direction of the hospital 44 seconds before an explosion there

The analysis of that and other videos, in addition to expert review of imagery of the blast site, provides circumstantial evidence that could bolster the contention by Israel and the U.S. government that a stray rocket launched by a Palestinian armed group was responsible for the Oct. 17 explosion.

At the same time, no visual evidence has emerged showing a rocket hitting the hospital grounds, and the evidence reviewed by The Post does not rule out the possibility that an unseen projectile fired from somewhere else struck the hospital grounds.

None of the more than two dozen experts consulted by The Post was able to say with certainty what kind of weapon struck the hospital grounds or who fired it. But munitions experts agreed that the damage at the hospital was consistent with a rocket strike. They said it was not consistent with an airstrike, which would have caused much greater destruction, or with an artillery strike, which would have left substantial fragments and probably not caused the massive fireball seen in videos.

In addition, The Post’s analysis found that a key video filmed and aired by Al Jazeera, which the Israeli and U.S. governments have cited as evidence that a rocket failed and landed on the hospital grounds, instead shows a projectile launching from a location miles away in Israel, near an apparent Iron Dome air-defense battery. Experts said that the widely circulated video probably showed an Iron Dome interceptor missile that collided with a rocket more than three miles from the hospital and most likely had nothing to do with the hospital explosion.

The U.S. Office of the Director of National Intelligence declined to comment on The Post’s specific findings, including the geolocation of the possible interceptor’s launch site inside Israel. A spokesperson said they had “high confidence” that the hospital explosion was caused by a rocket launched by “Palestinian militants,” based on unpublished intercepted phone conversations, an analysis of the damage at the hospital, and four publicly available videos. They said the Al Jazeera video was one of the four they relied on but did not share the others.

Jonathan Conricus, an Israeli military spokesman, said Israel did not make any interceptions around that time but did not directly respond to The Post’s visual analysis.

The lack of direct evidence has made it difficult to prove definitively who fired the munition that exploded at al-Ahli Hospital and illustrates the limits of trying to remotely investigate incidents in war zones without on-the-ground access.

Palestinian rockets are unsophisticated and not guided, and they carry propellant to power their motor, experts said.

Markus Schiller, a Munich-based rocket and missile expert, said he estimated that it would have taken one of the standard Qassam-model rockets used by Palestinian armed groups between 25 and 45 seconds to reach the hospital from the launch site, depending on factors including launch angle.

Ferenc Dalnoki-Veress, a professor at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies and scientist-in-residence at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, said that his findings conformed with Schiller’s and that the rockets would have taken between roughly 26 and 37 seconds to reach the hospital.

The barrage seen in the videos, which included more than a dozen visible rockets, begins 44 seconds before the hospital explosion and lasts for 14 seconds, meaning many or potentially all of the rockets could have reached the hospital in time for the explosion. There was no visual evidence to prove that any of them failed and crashed.

The blast

Video filmed from a building about 500 feet southeast of the hospital captured the high-pitched scream of a projectile speeding by just before the explosion.

The Post sent that video and another that captured the moment of the explosion to multiple audio forensic experts for review. Rob Maher, a professor at Montana State University, said that the increasing frequency produced by the incoming projectile indicates that it was accelerating.

Acceleration could imply that the projectile was falling vertically, gaining speed from gravity, he said, adding that that would be more consistent with a malfunctioning rocket plummeting from the sky, according to acoustic analysis, than an object moving horizontally.

The impact on the grounds of al-Ahli Hospital caused a large explosion and fireball to erupt.

Marc Garlasco, a former Defense Department battle damage assessment analyst and U.N. war crimes investigator, said the blast required a “substantial” amount of explosive payload and fuel accelerant, like that carried by a malfunctioning rocket.

Flames engulfed the hospital’s courtyard, where hundreds of people had reportedly been sheltering in the hope of avoiding airstrikes. A video taken in the immediate aftermath shows dozens of bodies strewn around the courtyard.

The aftermath

Photos show members of the Palestinian police explosives ordnance disposal unit examining a crater caused by the blast that night. The morning after the strike, Palestinian journalists and civilians began posting videos and photos of the scene. No remnants of the munition that caused the blast were evident in the images.

They showed more than a dozen incinerated vehicles, including one that had flipped onto its roof, in the hospital’s parking lot.

Burned vehicles

An aerial view of al-Ahli Hospital in Gaza City on Oct. 18 in the aftermath of an overnight blast. (Shadi Al-Tabatibi/AFP/Getty Images)

Burned vehicles

An aerial view of al-Ahli Hospital in Gaza City on Oct. 18 in the aftermath of an overnight blast. (Shadi Al-Tabatibi/AFP/Getty Images)

Burned vehicles

An aerial view of al-Ahli Hospital in Gaza City on Oct. 18 in the aftermath of an overnight blast. (Shadi Al-Tabatibi/AFP/Getty Images)

The buildings surrounding the courtyard had sustained relatively light damage, including shattered windows and tiles blown off roofs.

The small crater, measuring nearly three feet wide, was located in the parking lot between two grassy lawns where civilians had been sheltering. A spray-like fragmentation pattern in the ground extends from the crater in one direction, but experts did not agree on its significance.

Portions of a metal and concrete fence nearest to the crater were broken and bent, and nearby trees appeared to have been burned.

Impact site

Fragmentation pattern

Two video frames show the complete length of the fragmentation pattern around the impact site. (Mohmmed Awad)

Impact site

Fragmentation pattern

Two video frames show the complete length of the fragmentation pattern around the impact site. (Mohmmed Awad)

Impact site

Fragmentation pattern

Two video frames show the complete length of the fragmentation pattern around the impact site. (Mohmmed Awad)

More than half a dozen experts who independently reviewed imagery of the scene said the lack of major blast damage, such as collapsed buildings, as well as the relatively small size and shape of the crater, ruled out the possibility of the kind of airstrike Israel has carried out elsewhere in Gaza since Oct. 7.

“I can categorically say this wasn’t an airstrike,” Garlasco said.

Garlasco noted the large amount of what he called “localized thermal damage,” meaning destruction from fire, which he said is not common in airstrikes. Such a scene, he said, is instead more consistent with a munition “with a lot of fuel in it” falling to the ground prematurely and igniting along with its warhead. That would create a flash fire that ignited the compound with concentrated rather than widespread damage, Garlasco said.

The size of the crater and the blast bore some similarities to an impact from a 155-millimeter artillery round, a munition in the Israeli arsenal, said Chris Cobb-Smith, a security consultant and former artillery officer in the British army. But other weapons could do the same, and an artillery round would not have produced the fireball seen in the blast videos, he said.

On Oct. 14, just three days before the hospital explosion, hospital officials said the facility had been struck by another projectile, and a video filmed inside showed a 155mm artillery illumination shell sitting on the floor of a room with a large hole in the wall. Illumination rounds are not fired directly at targets and descend on a parachute to signal, illuminate areas or mark targets, while the body of the shell falls from the sky. The shell landed in an ultrasound room, wrote the man who posted the video, an Anglican pastor who works for the diocese associated with the hospital.

Conricus, the Israeli military spokesman, said that the munition on Oct. 14 appeared to be a 155mm illumination round but that the hospital had not been targeted.

“It was definitely not struck on purpose,” Conricus said. “If an artillery round landed there, then it was probably a result of it falling or landing after having been fired, but definitely not targeting the hospital.” The Israeli military did not fire a 155mm round in the area of the hospital on Oct. 17, the day of the explosion, he said.

A misinterpreted video

The Israeli and U.S. governments, and some news organizations, pointed to a video filmed and aired by Al Jazeera the night of the blast that seemed initially to show a possible rocket fly near the hospital and explode in midair seconds before the hospital explosion. The Israeli military cited the video in multiple interviews. U.S. intelligence officials said their analysts had also relied on that video.

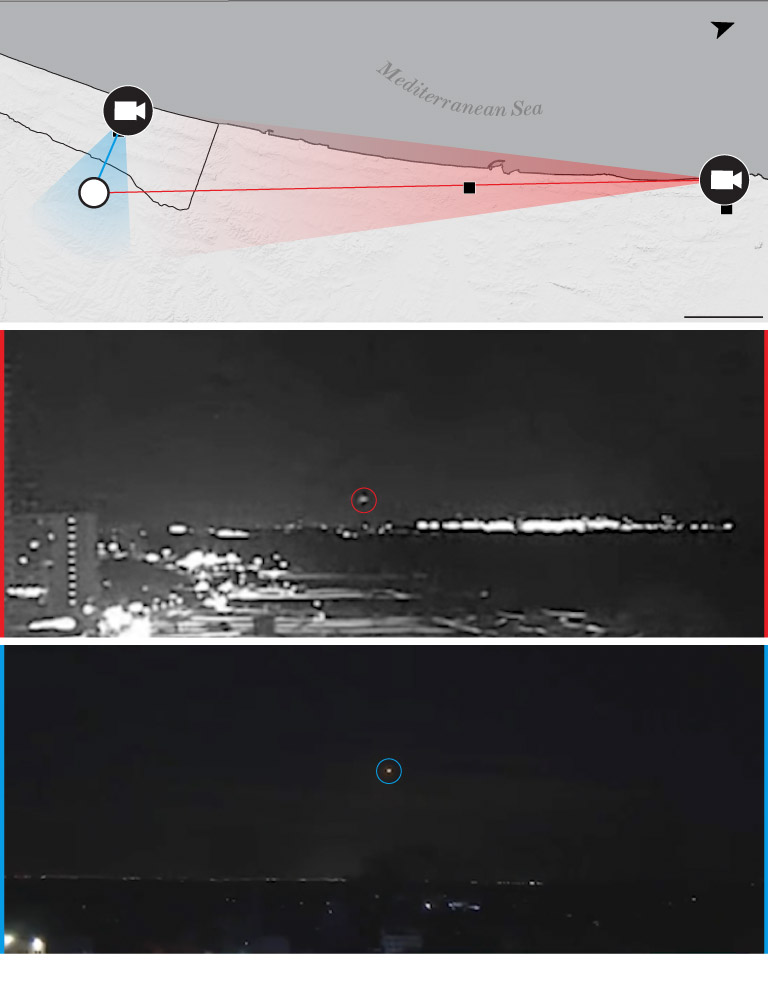

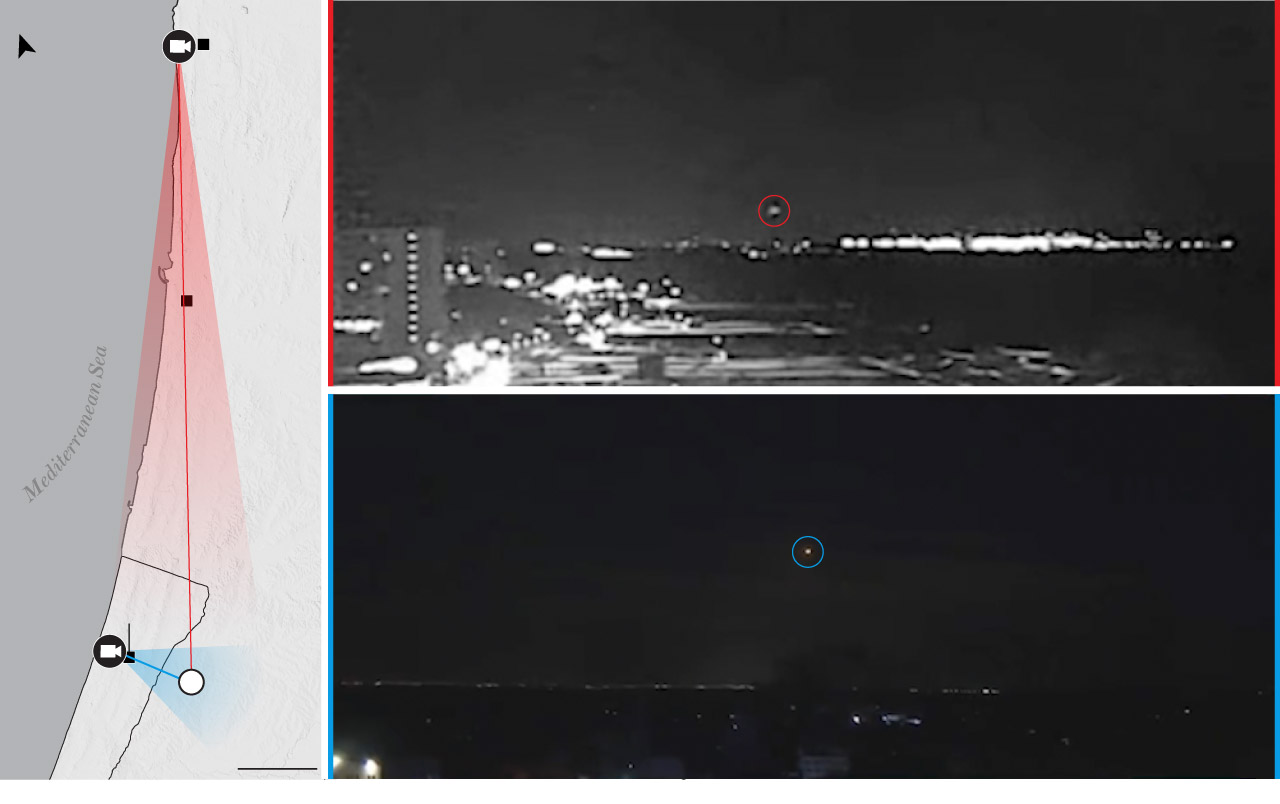

But after analyzing multiple videos, The Post found that the projectile in question had actually launched from a point inside Israel near a likely Iron Dome missile defense site, and experts said it was probably an interceptor missile that had nothing to do with the hospital blast.

About 20 seconds after the rocket barrage began, the live camera in the Tel Aviv suburb captured the lone projectile rising far to the east, as did a video filmed by a cameraman on a Gaza City rooftop.

The Post used these two videos to triangulate the origin of the projectile to a point about 2½ miles inside Israel and confirmed the location with the video obtained from Keshet 12 News. The origin point was first identified by independent open-source investigators who posted their findings on X and Discord.

N

GAZA

B

al-Ahli Hospital

A

Ashdod

Bat Yam

Estimated

interceptor

launch

location

ISRAEL

5 MILES

A

B

Video credit: Youtube / Al Jazeera

THE WASHINGTON POST

N

GAZA

B

al-Ahli Hospital

A

Ashdod

Bat Yam

Estimated

interceptor

launch

location

ISRAEL

5 MILES

A

B

Video credit: Youtube / Al Jazeera

THE WASHINGTON POST

A

N

Bat Yam

A

Ashdod

ISRAEL

B

al-Ahli Hospital

Estimated interceptor launch location

B

GAZA

5 MILES

THE WASHINGTON POST

Video credit: Youtube / Al Jazeera

A

N

Bat Yam

A

Ashdod

ISRAEL

B

Ashkelon

al-Ahli Hospital

Estimated interceptor launch location

B

GAZA

5 MILES

The projectile’s origin location was in the vicinity of an Israeli military site, satellite images show. Experts said the site, imaged by Planet Labs on Oct. 20, has features that are consistent with known examples of Iron Dome missile batteries, including blast walls arranged directly next to launchers.

Blast wall

Blast wall

Potential launcher

200 FEET

THE WASHINGTON POST

Satellite © Planet Labs 2023

Blast wall

Blast wall

Potential launcher

200 FEET

THE WASHINGTON POST

Satellite © Planet Labs 2023

Blast wall

Blast wall

Potential launcher

200 FEET

Satellite © Planet Labs 2023

THE WASHINGTON POST

About 15 seconds after launching, and after changing its direction and arcing toward the west, the projectile that originated from the vicinity of the suspected Iron Dome location exploded in midair.

Five experts who reviewed the videos told The Post that the projectile appeared to be a Tamir interceptor missile fired by Israel’s Iron Dome system, based on its behavior and launch location.

“All we are seeing is the missile interceptor,” said Dalnoki-Veress. “These interceptors are then constantly changing their course to correct for the expected intercept point in time and space.”

Unlike the unguided rockets fired by Palestinian armed groups, which follow ballistic trajectories, the missile’s snaking path through the sky before exploding showed a “clear non-ballistic trajectory you expect from the Tamir interceptor,” Dalnoki-Veress said.

Justin Bronk, a senior research fellow at the U.K.-based defense and security think tank Royal United Services Institute, interpreted the footage differently and wrote in an email that it captured “a single visible rocket motor that shows a sudden, quite violent course change that would be consistent with a control surface failure, followed by a shower of sparks consistent with a structural breakup in flight a few seconds later.”

A spokesperson for the Office of the Director of National Intelligence told The Post that multiple videos showed “a rocket or missile experiencing a probable in-flight failure about 10 seconds after launch” and that the explosion at al-Ahli Hospital shortly thereafter was “almost certainly the falling warhead.” The spokesperson did not identify the projectile’s precise origin point in Gaza.

The five experts agreed that there was no evidence to connect the likely interception to the hospital blast and that the two events probably had no relationship to each other.

The explosion and fireball erupted at the grounds of the hospital seven seconds after the apparent interceptor missile exploded in midair. The Post triangulated the location of the likely intercept explosion to a point about a mile inside the Israeli border and about 3½ miles east of the hospital.

The seven seconds between the midair explosion and the hospital explosion miles away was not enough time for debris from the intercept to have impacted the hospital, Schiller said. Any object at the site of the midair explosion would have had to travel at more than 500 meters per second, a supersonic speed, which “is quite impossible,” he said. Schiller said the culprit was more likely an unrelated rocket that was malfunctioning and “hit the hospital grounds just a few seconds after that intercept event.”

Shane Harris, Sarah Cahlan, Joyce Lee and Dalton Bennett in Washington and Sarah Dadouch in Beirut contributed to this report.