A previous version of a photo caption at the top of this story incorrectly said an earthquake in Alaska was in 2019. It was in 2018. The caption has been corrected.

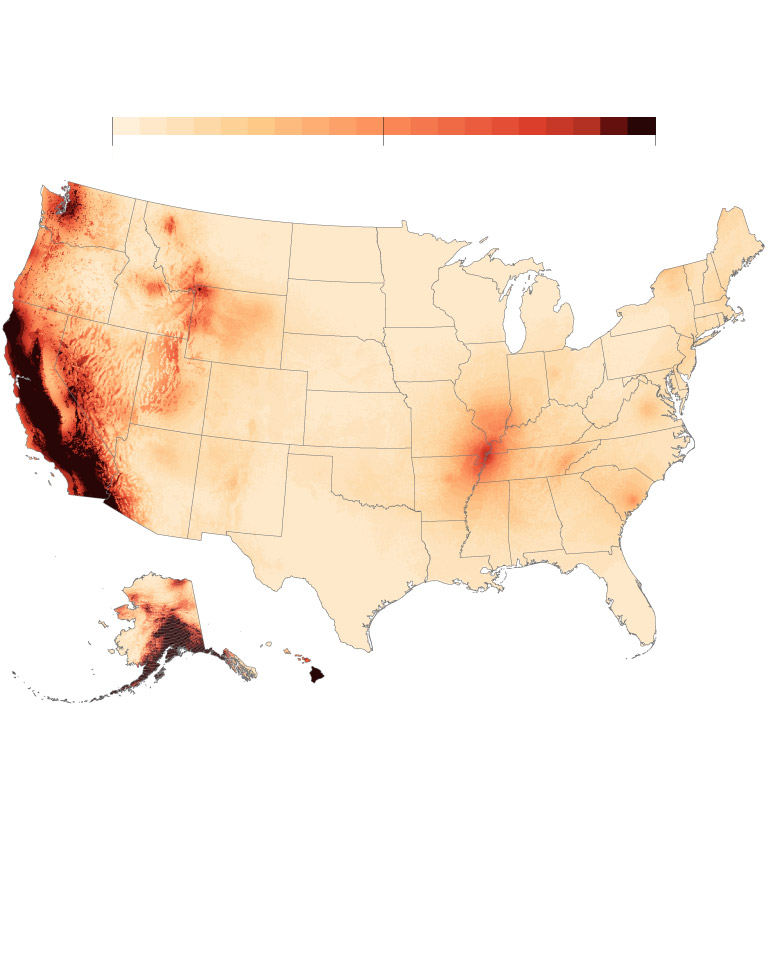

Perhaps more surprising, part of the Mississippi Valley has up to a 90 percent chance of experiencing damaging shaking. Central Virginia and Charleston, S.C., have up to a 50 percent chance. Moderate to large earthquakes in these areas would reverberate to large population centers like D.C., Boston and New York City.

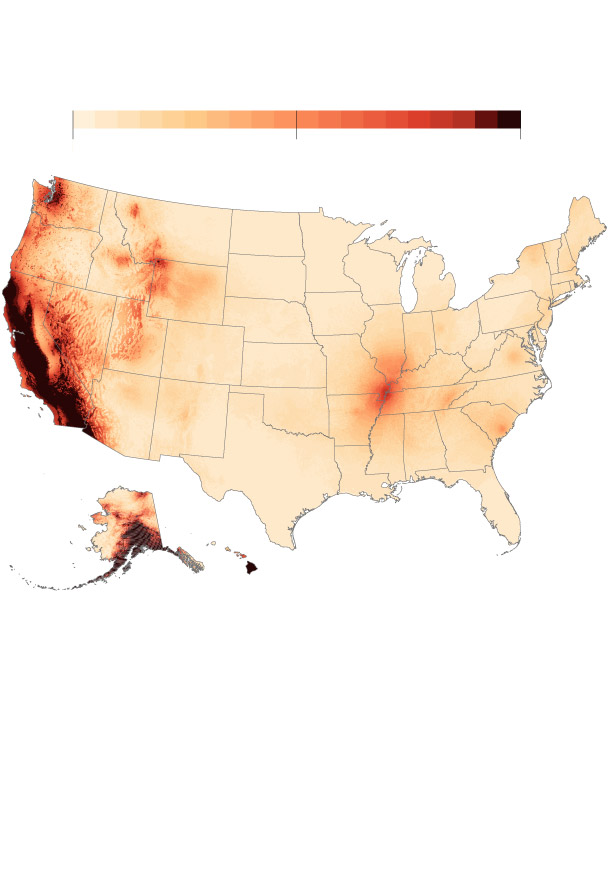

Risk of shaking from a damaging earthquake in the next century

100%

0

50

Note: This map shows the maximum risk of damaging shaking caused by a moderate earthquake in the next century

Source: The U.S. Geological Survey’s 2023 U.S. National Seismic Hazard Model

Veronica Penney/ THE WASHINGTON POST

Risk of shaking from a damaging earthquake in the next century

0

50

100%

Note: This map shows the maximum risk of damaging shaking caused by a moderate earthquake in the next century.

Source: The U.S. Geological Survey’s 2023 U.S. National Seismic Hazard Model

Veronica Penney/ THE WASHINGTON POST

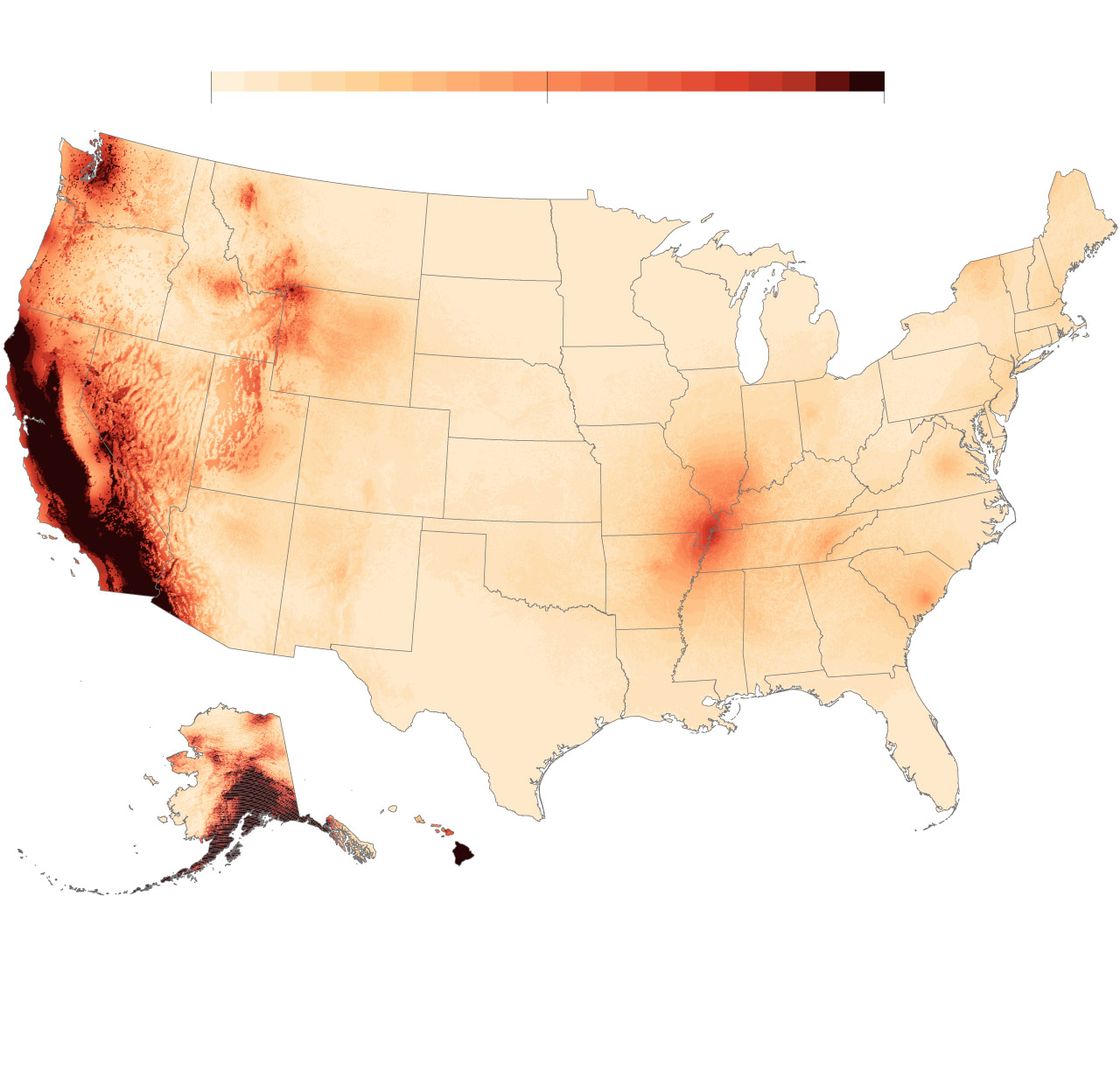

Risk of shaking from a damaging earthquake in the next century

0

50

100%

Note: This map shows the maximum risk of damaging shaking caused by a moderate earthquake in the next century.

Source: The U.S. Geological Survey’s 2023 U.S. National Seismic Hazard Model

Veronica Penney/ THE WASHINGTON POST

The damage could be anywhere from a crack in a building to a full collapse, although most of the modeled hazard would be slight, said Mark Petersen, lead author of a new study detailing the model. The model shows shaking from a moderate sized earthquake, magnitude 5.

“Many states have already experienced damaging earthquakes of magnitude 5 and greater” over the past two centuries, said Petersen. “We want to be able to prepare infrastructure and people for the shaking that we think can occur in their lifetimes.”

While no one has ever predicted a major earthquake, scientists can forecast where earthquakes are more likely to occur through seismic hazard models. Based on the best available scientific studies, historical geologic data and data collection, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) releases new risk assessments for the nation every few years.

The 2023 model, the biggest update in five years, is the most comprehensive analysis of active faults, past earthquake activity and geological factors that can affect seismic activity.

“It’s been almost 120 years (1906) since we’ve had a large earthquake make a direct hit on an urban area,” Greg Beroza, a professor of geophysics at Stanford University who was not involved in creating the model, wrote in an email. “The US has grown so much and so much has changed in the world since then, that the next such earthquake is likely to bring some unanticipated consequences.”

Earthquakes are expected to cost the United States $14.7 billion each year due to ground-shaking-related damage to buildings, according to USGS and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). FEMA advises people to have an earthquake plan in place and follow safe practices, like dropping during the event and evacuating after.

Greatest risks in the United States

Earthquakes are caused by a sudden slip of a fault or fracture in Earth’s crust. Tectonic plates are constantly moving slowly, but their rough edges often contain faults and get snagged. As the plates get caught, stress builds. When the stress grows too big, it can overpower the frictional forces holding the plates together. When the plates are released, the pent-up energy is released and sends seismic waves in all directions — shaking Earth’s surface.

Locations on the boundaries of these tectonic plates showed the greatest risks, unsurprisingly, according to the model. Alaska and California, the most seismically active zones in the nation, have more than a 95 percent chance of feeling shakes from at least a slight earthquake in the next 100 years.

Hawaii’s Big Island also had more than a 95 percent chance of earthquake shakes, but the seismic activity is often linked to volcanic eruptions — loosely called volcanic earthquakes. In 2018, a magnitude 6.9 earthquake occurred a day after the Kilauea volcano started to erupt.

Increasing risks in the central and eastern U.S.

Earthquakes are less common in the central and eastern United States, but they still occur and pose risks.

“The biggest change in risk appears to be in the Eastern Seaboard,” Beroza wrote in an email. “The earthquake hazard is increased, though still moderate there compared to places like California; but, the concentration of people and built infrastructure there is very high, so that’s a lot of exposure.”

But quantifying the risk in the central and eastern United States is a slightly different story because their seismic source isn’t as obvious. They aren’t located at the boundary of a tectonic plate and don’t have volcanic earthquakes.

These earthquakes happen within a tectonic plate, thought to be largely geologically quiet. Scientists generally think they occur because old fault systems are reactivated, perhaps through upward movements from the mantle. The old systems were created from past tectonic movement that broke up and reformed the plates, leaving remnants of these ancient faults and tectonic plates beneath the surface. These older faults are hard to detect.

“We don’t know very much about the faults in the central and eastern U.S. because glaciation and other erosion has taken the evidence of those earthquakes away in many cases,” said Petersen, a geophysicist at USGS. Other evidence of faults “have been cleaned off and covered up by buildings.”

Because the faults are hard to see, scientists look for other evidence of a past earthquake. When an earthquake shakes the ground, it causes soils, sand and water to vent to the surface — a process known as liquefaction. Scientists look for these large sandy deposits on the surface, known as sand blows.

“What researchers have is the evidence of past earthquakes that they can determine how often the earthquakes happen,” said Petersen. “We can use the seismicity to project the kinds of earthquakes that we think can happen in the central and eastern U.S. and those effects.”

In the central United States, the most prominent hot spot is the New Madrid seismic zone in the Mississippi Valley — a small sliver that has a 75 to 95 percent of experiencing earthquake-related shaking. The seismic zone branches into southeastern Missouri (near the town of New Madrid), northeast Arkansas, southwestern Kentucky and northwest Tennessee.

Faults in the region are hard to see on the surface because they’re buried under river sediment, but researchers have found sand blows. The sand blows probably originated from large earthquakes (magnitude 7 and 8) in the winter of 1811 and 1812, which destroyed several areas along the Mississippi River and changed the topography.

A standout location on the East Coast is Charleston, S.C., in the Coastal Plain, which is one of the most seismically active areas in the eastern United States. In the Coastal Plain, underlying rocks are faulted or fractured from the breakup of tectonic plates — weakening that area of that plate. In 1886, a magnitude 7.0 earthquake hit Charleston, killing 60 people and damaging buildings, making it the most damaging quake in the eastern United States.

In more recent memory, Mineral, Va., experienced a magnitude 5.8 earthquake in 2011 that shook the East Coast and damaged the Washington Monument in D.C. The earthquake occurred in the Central Virginia Seismic Zone, laced with faults likely formed from plates colliding hundreds of millions of years ago. Adding new data about the seismic zone since the last model, the update bumped the location’s chance of feeling earthquake shaking to 25 to 50 percent.

Overall, Petersen and more than 50 scientists and engineers added 500 new faults in the western United States and Alaska and a dozen or so in the eastern United States in the updated model. They also added soil depth models in regions, as some soil types can magnify earthquake shaking. In some cases, they used supercomputers to simulate past earthquakes and observe the subsequent shaking. They also incorporated GPS data, which tracks deformations in the faults. It includes more than 130,000 earthquake records in the United States at a magnitude of 2.5 or greater.

Quantifying earthquake hazard in this way, Beroza said, is foundational to the country’s efforts to mitigate risk. “We’re constantly learning more, so it’s important to capture that improved understanding in hazard characterization,” he said. He said this update is a “very welcome development.”

There are still many faults in the eastern United States that are not included in the model, Petersen said. The biggest reason is the lack of evidence of movement on those faults because they’ve been eroded or covered up. But he thinks the general hot spots on the East Coast will probably persist even with new data.

“We try to make the best model we can that can be used in building codes, insurance rates, planning by FEMA and by states,” said Petersen. “We want to produce more resilient communities so that when an earthquake does strike, we can quickly recover.”